"I have come to grips many, many, many years ago that only through love can we make a difference," shares United Methodist deaconess Clara Ester. "We can actually change things if we love."

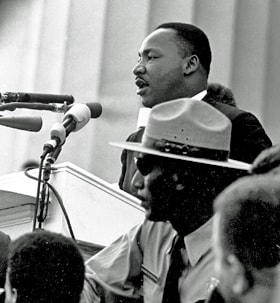

Ester learned this important lesson from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., leader of the civil rights movement in the United States.

"Love takes a lot of effort and work," Ester continues, "but that's the way God wants us to go, and that was the life that Dr. King led."

Love, justice, nonviolence

"Being clergy he knew the importance of love," Ester says of King, "and he wanted to deal with major issues and concerns that people were going through in a justice way. But he did it through love and nonviolence. That was his life."

Growing up in Centenary Methodist Episcopal Church in Memphis, Tennessee, then pastored by civil rights leader the Rev. James Lawson, Ester saw a connection between King and her faith.

"He led the life and stood up for things like Jesus did when he was on earth," she explains. "The marginalized people were the people Jesus hung out with. People that were not your favorite folks to be around were folks you found Jesus with…. Dr. King stood up and spoke out for the same marginalized people. He tried to change structures that would make that world better."

Love takes time

Ester hadn't always seen things that way. "I had a lot of hate within me when I saw how people could be treated," Ester confesses. Love and nonviolence seemed a slow way to affect change.

"I was a junior in college," she remembers. "I heard both sides… but being young, 19 or 20 years old, I wanted everything to end as rapidly as possible."

On the evening of April 4, 1968, things changed. Ester had just arrived at the Lorraine Motel when King came out of his room and started talking to people in the parking lot. A shot rang out. King's assassination was a turning point for Ester.

"Witnessing his death. Seeing him on that balcony. Hearing him the night before talk about, 'I may not get there with you, but we as a people will make it to the Promised Land.' Recognizing more and more about his commitment to the nonviolent process. There was something about being over his body that said, 'You need to change your hate. You need to love.'"

A God-assigned responsibility to reach out

Reflecting on the call to love our neighbors, Ester references Jesus' parable of the Good Samaritan where a man is mugged and left by the side of the road (Luke 10:25-37). Two religious leaders approach, whom Jesus' first listeners would have expected to be the people to do something, but they each cross the street to avoid the injured man. The third person who comes down the road is a Samaritan.

This is not the person anyone would have expected to help out. The gospel of John tell us, "Jews and Samaritans didn't associate with each other" (John 4:9). Yet in Jesus' story the Samaritan goes to extraordinary lengths to care for this stranger.

After concluding the parable, Jesus tells those who've head the story, "Go and do likewise." On the balcony that day, Ester heard that same call.

"Witnessing his death made me recognize that I had a responsibility not to ever step over anybody, or walk on the other side of the road. If there were people that I was aware of on the path that I was going, I had a God-assigned responsibility to reach out and try to help make their world better."

"That's where we all should be," she continues, "If we all did that through love and compassion, we would be living in a greater society than we live in today."

A life of service

Immediately following King's assassination, Ester left college. She went to Marks, Mississippi to work on the second Poor People's Campaign, a march from Mississippi to Washington, D.C. planned by King. Marks was chosen because it was considered "the poorest town in the poorest county of the poorest state in the nation" (Mississippi Stories).

Later, Ester would return to school and finish her degree. She served as a deaconess in The United Methodist Church, working for people in need throughout her career. In 2006, she retired as executive director of Dumas Wesley Community Center, a mission institution in Mobile, Alabama supported by the United Methodist Women.

That day at the Lorraine Motel shaped her ministry. "This man was willing to love until this moment when a bullet took his life. He was willing to work and stand up and fight in a nonviolent way," she teaches. "That was the least that I could do."

"After that," she says, "it was strictly nothing but, 'What can I do to help somebody else? What can I do to make life better? What can I do or what can I give to change the narrative of what's taking place in this person's life today?' It was a turning point in my personal life for me to reflect on the direction I could have been in, and the direction I needed to go."

Joe Iovino works for UMC.org at United Methodist Communications. Contact him by email.

This story was published January 20, 2019.