In the recent confirmation hearing for Amy Coney Barrett, Republican Senator, John Kennedy, in response to Senator Kamala Harris, made the following comment:

We disagree. She (Senator Harris) thinks America is systemically racist. I don't. I think our history is the best evidence of that. I don't think we are a racist country. I think we are a country that has some racists in it. But I'm very proud of the fact that our country . . . in 150 years—which in the grand scheme of life, death, and the resurrection is the blink of an eye—we’ve gone from institutionalized slavery to an African American president. We passed . . . civil rights laws in 1869, 1871, 1957, 1961, 1965, 1990, 1991. I'm pretty proud of that.[1]

Senator Kennedy is not alone in this view of America. A recent Pew Research study indicates that only 26% of Whites believe that the legacy of slavery continues to affect the position of black people in America today compared to 59% of blacks.[2] The statistics are even more telling when factoring for religious views. According to the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) 60–70% of White mainline and evangelical Protestants disagree that the history of slavery and discrimination continue to have an influence on social and economic mobility for blacks.[3]

All of this reflects the dominant picture of America, one that is essentially non-racist, having surmounted issues of slavery and segregation in short order, “in the blink of an eye,” according to Senator Kennedy. But as I previously noted, this dominant picture obscures the facts, making it more difficult to see the lines that make up the picture of systemic racism in America. Switching our focus from one to the other requires a Gestalt switch to see how the lines form a different picture.

Gestalt Switch: When an interpretation of experience changes from one perception to another. Much like seeing a “magic eye” picture.

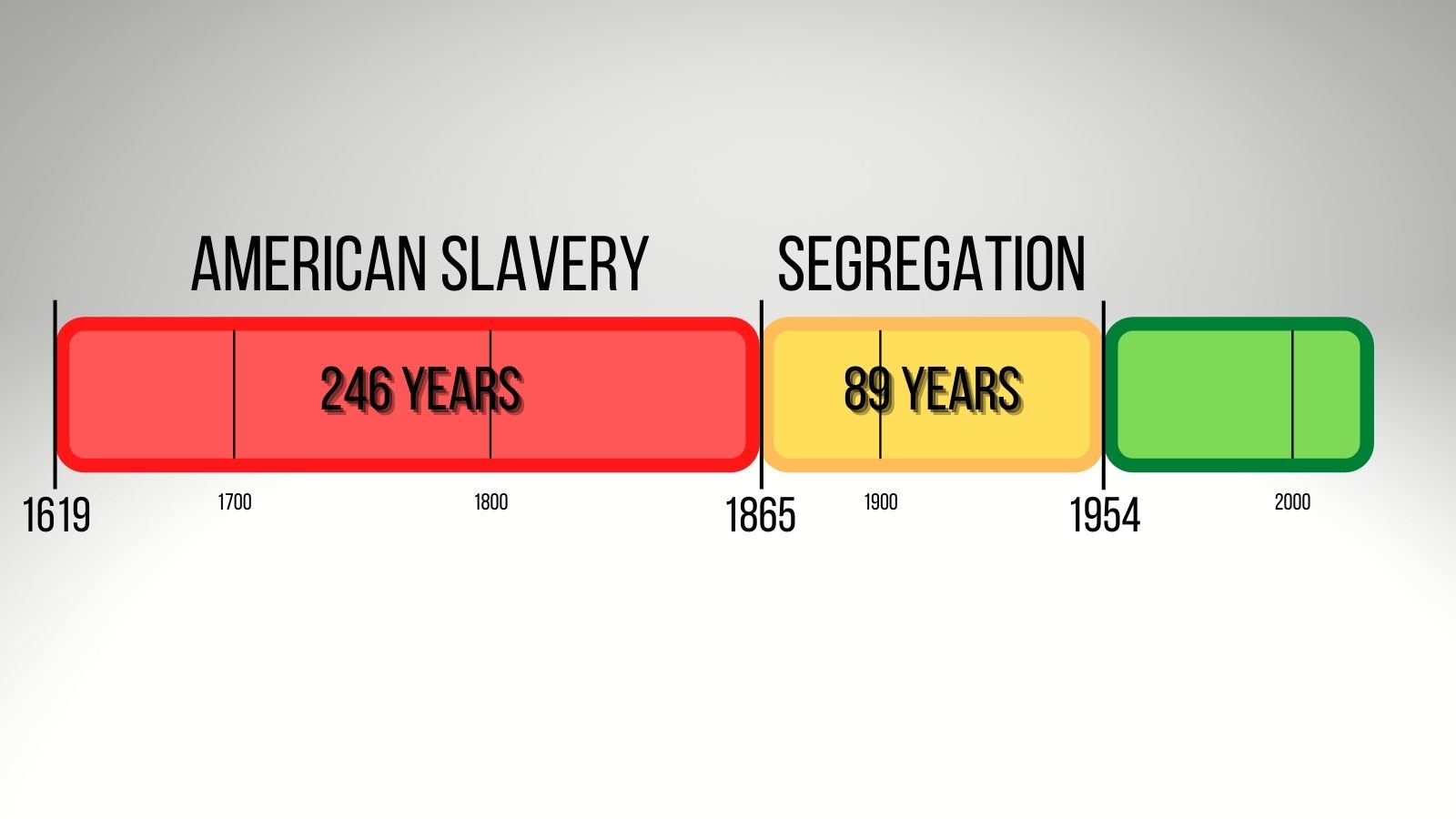

One of the clearest starting points for seeing the Gestalt switch on race in America begins with an acknowledgement not only of slavery and segregation, but of how long these institutions lasted and how interwoven they are into the fabric of America. To put this in historical perspective, slavery began in 1619 (earlier, depending on how you calculate it) and lasted lawfully (de jur) until 1865, though in practice (de facto) it continued long after. This means that the institution of slavery lasted 246 of the 244 years that America has been a country. Of course, this is screwy math, but the point is clear. Slavery in North America has existed longer than the United States has been a country. Add to this the additional hundred years of federally-sanctioned segregation (1865-1965, if you include the ten extra years it took to win the right of African Americans to vote) and you wind up with nearly 350 years of de jur systemic oppression out of a total of 244 years. That means that slavery and segregation have constituted 143% of our country’s history—even screwier math! Compare this to the past fifty-five years of “supposed” racial equality and the sheer weight of history speaks against the dominate picture of America as essentially non-racist.

Moreover, slavery was a central component of the economic engine of America and continues to account for disparities between blacks and whites, today, on issues of wealth, education, and opportunity. While the centrality of slavery in the southern economy is well documented, what is often overlooked is its role in shaping the economy of the entire country. Seth Rockman, author of Slavery’s Capitalism, argues that cotton constituted 50-60% of the export profits for the entire country and was the primary commodity “at the heart of the Industrial revolution.”[4] It was the slave industry, more than any other industry, that placed America in a position of dominance in the global economy and eventually paved the way for “more recognizable iterations of industrial and financial capitalism of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.”[5] Thus, many of the privileges that we experience today, particularly as Whites, are due in no small measure to this institution. By the same token, because generations of blacks were kept from accumulating capital, land, or education, many of our Black communities have been kept from reaping the same benefits, placing them in a position of disadvantage from the start.

Most damning of all, however, is the fact that these practices were firmly rooted in ideological commitments that were a part of the European and early American outlook from the beginning, and ensconced in the defining documents of the country. The Corner Stone Speech, for example, was an address made by Alexander H. Stephens in 1861 in Savannah, GA, following the secession of the southern states and a few weeks prior to the Civil War. It highlighted the strength of the Confederate constitution, arguing that whereas the former United States constitution “rested upon the assumption of the equality of the races,” the “new government is founded on the opposite idea . . . the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.”[6] White supremacy, then, was the foundation of the Confederate constitution, not incidental to it.

Lest we absolve the northern states, however, consider the doctrine of separate but equal, passed by the United States Supreme Court only thirty-five years after the Corner Stone Speech, which served as federal justification for the entrenchment of Jim Crow laws and practices of segregation throughout the country. Consider, too, the 13th and 15th Amendments. While the first is touted as abolishing slavery, it contains a significant caveat—“except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This proviso left the door open and was used to justify the practice of convict leasing shortly after abolition and, many argue, continues to be used as justification for the criminal justice system today.[7] Second, while the 15th Amendment of 1870 appears to ban “racial discrimination in voting,” bear in mind that Martin Luther King, Jr. was still fighting for that actual right up to 1965, almost a hundred years later!

What is our responsibility as Christians in all of this?. In the same way that there is a dominant picture of America that requires a Gestalt switch for us to see racism, there is a dominant way of viewing Scripture that also needs to be switched in order to see our responsibility as Christians in issues of race. In the meantime, the best thing we can do as concerned Americans is vote. We can march in the streets, we can post our convictions on social media, we can lament our concerns about the state of our nation, but if we don’t elect people who represent these concerns, we will never see substantial change. In our country change comes through the voice of the governed and the loudest voices are the ones represented in the voting booth. While the presidential election has come and gone, the senate elections are still underway. I encourage you to vote your conscience.

[1] Senator John Kennedy, The Confirmation Hearing for Amy Coney Barret, October 14, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4qAGlCKKHL4

[2] Juliana Menasce Horowitz, “Most Americans say the legacy of slavery still affects black people in the U.S. today,” Pew Research Center, 2019. https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/17/most-americans-say-the-legacy-of-slavery-still-affects-black-people-in-the-u-s-today/?amp=1

[4] Seth Rockman, Slavery’s Capitalism: A New History of American Economic Development (Pennsylvania, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016) 5-6.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Alexander H. Stephens, “Speech Delivered on the 21st March, 1861 In Savannah, Known as the ‘Corner Stone Speech,’” The Savannah Republican, 721.

[7] See: 13th, documentary, directed by Ava DuVernay, released September 30, 2016. Kandoo Films. Distributed by Netflix.