Though John Wesley preached about “honest industry,” many United Methodists may not know the hardworking preacher was the target of a counterfeit campaign, letters allegedly penned by the founder of Methodism, but with evidence indicating otherwise.

“Dear Brother Charles,” one such letter begins, a familiar salutation to Wesley’s beloved sibling.

What follows are words similar in tone to the ones found in the other 97 Wesley letters that belong to Pitts Theology Library at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology.

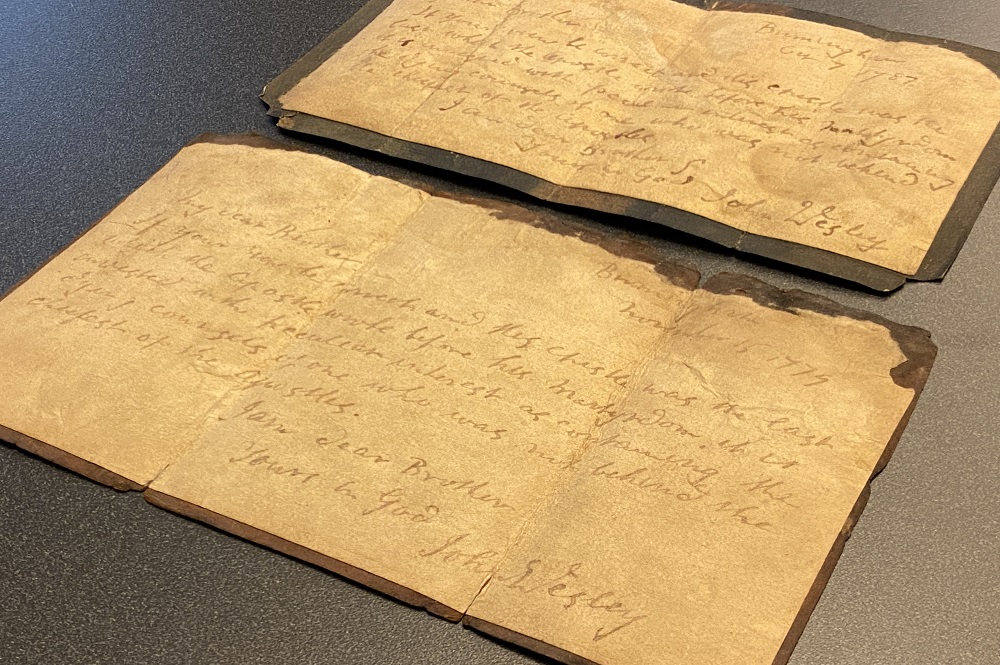

This letter, however, contains clues that it is a fake, one of less than 10 known forgeries, manuscripts bearing Wesley’s assumed signature but also indicating that other people – not the famed minister -- created the documents. Pitts owns two of the rare letters.

Before thinking that the Pitts archivists were duped, rest assured that the forged letters were purchased intentionally, meant to be part of a collection that serves to preserve, educate and be shared with the public.

“We wanted it because it was a forgery,” said Bo Adams, director of Pitts Theology Library. “There was this interest in the legacy of Wesley and that’s good, but it also can go in this negative way.”

By the time Wesley died in 1791, he had become celebrated, especially in religious circles.

“In the 19th century, to show you are a Methodist, you might have a picture or some pottery (bearing Wesley’s image). If you had an authentic Wesley letter, it would be framed,” says Randy Maddox, professor emeritus of Wesleyan and Methodist studies at Duke University and general editor of Wesley Works Project.

Fast forward a hundred years and Methodism was on the rise, Wesley, posthumously, was more famous than ever and his manuscripts were bringing in some money, explains Maddox as he sets the stage for why a counterfeit letter might be created.

“People forge things for different reasons,” explains Brandon Wason, Pitts’ Head of Special Collections. “This (letter) comes off as someone looking to make money. Someone was turning them out to sell them to unsuspecting people who were Wesleyan enthusiasts.”

“Today, an authentic John Wesley letter can sell for $6,000 to $10,000. In 1900, the forged letter would have needed to sell for enough to make it worth someone’s time. If it had been 10 pounds, it would have been worth it,” Maddox speculates.

Clues of fake letter

Wesley was a prolific letter writer, with 3500 catalogued by the Wesley Works Project and at least that many more that are in the hands of private collectors.

The two fake letters at Pitts (a total of four almost identical letters in the same handwriting have been discovered) share only slight differences in salutations, location and date.

After the opening, the letter reads:

“If your view be correct, and this epistle was the last which the apostle wrote before his martyrdom, it is invested with peculiar interest, as containing the dying counsels of one who was not behind the chiefest of the apostles.

I am, dear brother Charles, Yours affectionately, John Wesley.”

The location and date is listed as Birmingham, March 10, 1783. (It is known that Wesley was in Bristol, England, on this date.)

Aside from the conflict in locales, two of the most notable clues are how the letter opens and ends.

“There are no known letters in which John addressed his brother in his way,” Maddox says, “and the closing is wrong. John never once said, ‘Dear Brother Charles.’ Always ‘Dear Brother.’ And generally closed letters with simply ‘Adieu’ or ‘Farewell.’”

Wesley’s journals were being published by this time, with lithographs of certain manuscripts made and sold for celebratory occasions. Gaining access to the authentic papers would have been difficult still, so having an original by which to compare a document someone was falsely being told was genuine would have been difficult. Also, the contents of these fake letters, it's noted, are purposefully vague.

“The person creating the letter is trying to avoid any way to make it easily seen that it isn’t authentic,” Maddox observes. “Somebody is just imagining what they think Wesley would say.”

Another clue is that the two letters are mounted on leather. Though this might have occurred during Wesley’s time as a means to preserve papers, Wesley never did this.

“We have a hundred letters of Wesley and none of them are mounted on leather,” Wason says. “Some were mounted to scrapbooks, but this would have been done by later collectors.”

The South Coast Forger

The identity of the forger is unknown, according to Maddox, but there is a consensus among experts that the fake letters were created by someone known as the South Coast Forger, a person who lived in the early 20th century in the Brighton, England, area. In addition to letters by Wesley, the South Coast Forger has been linked to forged letters by Charles Dickens and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the poet. A Dickens letter, forged by the South Coast Forger, was for sale by a U.K. shopping channel in 2021 for 10,000 pounds before its discovery as a fake.

With thousands of Wesley letters possibly still out in the world, verifying the authenticity of manuscripts and other artifacts is important, Maddox cautions, and suggests contacting a United Methodist library, such as Pitts, or the General Commission of Archives and History, for more information.

Crystal Caviness works for UMC.org at United Methodist Communications. Contact her by email.

This content was published March 4, 2022.