Note: To view the original image above full screen, click here

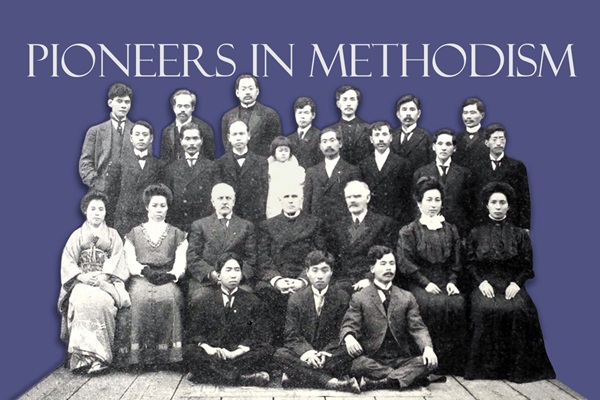

In Western cultures, a pioneer is often thought of as the first individual to do something or the leader of a new movement.

But the use of this word in earlier times suggests otherwise. The word “pioneer” derives from the French word “pionnier,” meaning “foot soldier.” A pioneer is someone who works diligently alongside others over a long period to achieve a common mission that prepares the way for others who will follow them.

The Rev. Zenro (Zenjiro) Hirota was a pioneer in Methodism in exactly this way. He was not the first Japanese-American to be ordained or received as a pastor in the Methodist Episcopal Church. That was Kanichi Miyama in the California Conference in 1887. Nor was he the first person to pastor what was already the largest church in the Pacific Japanese Conference, Pine Street Japanese Methodist Church in San Francisco. Neither was he the first to teach or be a leader at the Anglo-Japanese Training School attached to the church. But he was a pioneer as a “foot soldier” for Methodism, serving for 45 years among Japanese-speaking people in Hawaii, California and Washington.

Japanese Methodist Church in Hawaii

Article courtesy of Google Books

In the late 1800s, the first Japanese immigrants came to the United States following Japan’s emergence from isolation through newly established diplomatic relations. Zenro Hirota, born in Japan on Feb. 8, 1868, moved with his family to work in the sugar plantations in Hawaii while he was a young child. While there, he became a member of the Methodist mission (called the Sandwich Islands Mission, the name given to these islands by James Cook). He arrived in San Francisco in 1886 at age 18. Though he had come from Hawaii, he was considered an immigrant from Japan because Japan held the Japanese families in Hawaii under its protection at the time. This was prior to the United States annexing the Hawaiian Islands in 1898.

From the time of his arrival, Hirota became connected with the Methodists in San Francisco, and soon started on the path to becoming an ordained elder.

Soon after being ordained a deacon, now Rev. Hirota was sent to serve as an evangelist with the same Japanese Methodist mission in Hawaii where he had become Methodist. The 1891 Annual Report of the Methodist Episcopal Church Missionary Society notes, “Rev. Z. Hirota, an old member of the mission, went forth to the Sandwich Islands as an evangelist. He has been very successful. Scores have been converted and baptized.” His primary place of service while there was on Maui. There he became the founder of The Methodist Episcopal Church’s work to assist and evangelize people arriving on Maui from Japan.

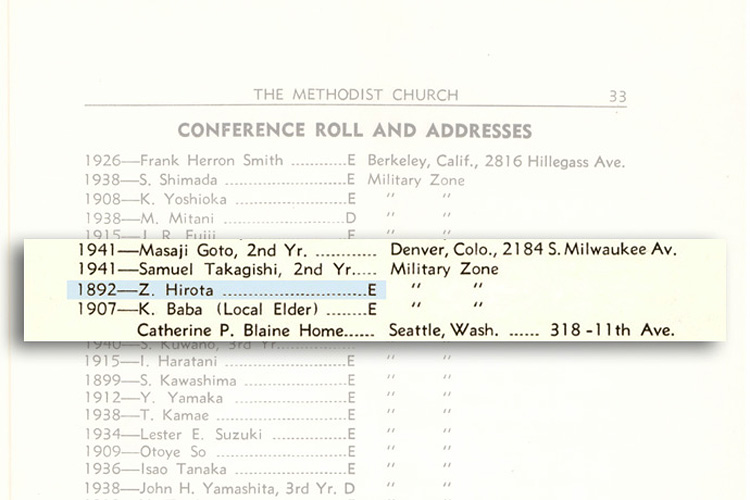

Rev. Hirota was ordained as an elder in the California Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1892 while continuing to split his time between Hawaii and California.

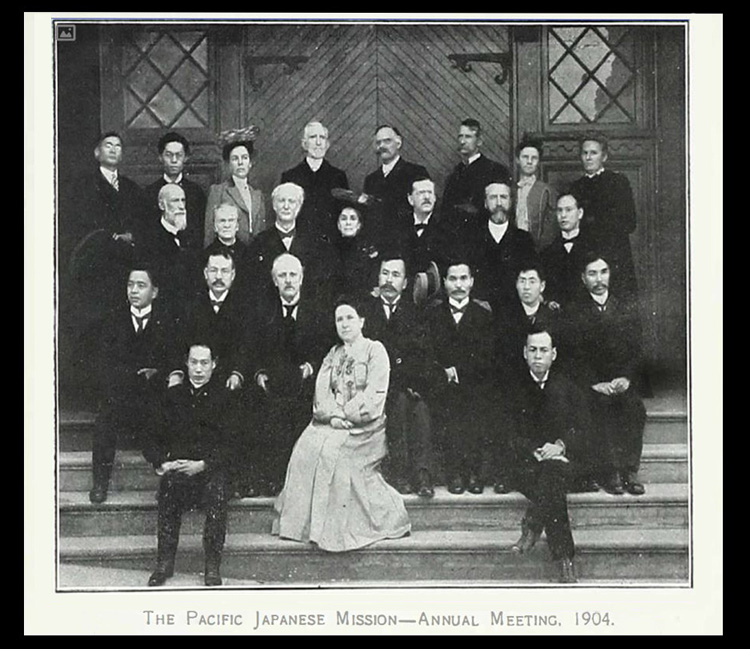

In the early 1900s, Rev. Hirota was sent to Pine Street Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church as pastor of the church and teacher (and sometime principal) of the Anglo-Japanese Training School related to the church. This school was regularly referred to by the Pacific-Japan Conference as “the oldest, largest, and one of the best Japanese schools in America.” The school provided training in English and Japanese to Japanese-speaking people in the San Francisco area, high school courses, and Christian religious education.

Also, during his time in San Francisco, Rev. Hirota met and married Toshi Wada, who had been visiting San Francisco from Japan. She could not legally immigrate to the U.S. when they met and married, but she was able to come to visit her husband from time to time. Their son, Albert, was born in California during one of her visits in 1904. Their daughter, Yoshiko, was born in Tokyo in 1908. The family was finally reunited permanently in San Francisco in 1909 when they were permitted to reside in the United States and seek citizenship.

In 1906, the devastating earthquake and fires in San Francisco caused massive destruction to Pine Street Japanese Methodist Episcopal Church, destroying the church, its offices, the school building, the dormitory, and the printing house (also overseen by Rev. Hirota) which provided the educational resources for the Japanese-American Methodist churches along the West Coast.

With Rev. Hirota’s leadership, church members preserved what they could. “At the time of the earthquake and fire in San Francisco, Dr. Herbert B. Johnson [head of the Japanese mission on the Pacific coast], living in Berkeley, was unable to get across the river. Native Japanese Christians in San Francisco, at the risk of life, entered the church, took some of the most valuable records, a picture of Bishop [Merriman] Harris, and the pulpit Bible, and carried them out in the back yard and buried them in the ground. After the fire was over these valuable records were found uninjured.” (Home Mission Trails, by Jay Samuel Stowell, Abingdon Press, 1920).

It was several years before the rebuilding was complete. During those years, while church attendance continued to grow, school enrollment declined because its temporary facilities were not as close to where Japanese families lived and were too small to accommodate as many students. Despite these setbacks, conference journals in these years praised Rev. Hirota for successfully continuing the church and school and reviving the publications work.

Bishops of Japanese descent

Able to reopen the school in 1908, enrollment began to increase just as another, and in some ways more difficult, challenge arose not only for Rev. Hirota’s church and the school, but also the entire Pacific-Japanese missionary conference and for Japanese people in America generally. Anti-Asian sentiments were making their way into policy and law. Already in 1907, Samuel Gompers, who had lobbied for years to curtail Chinese and Japanese immigration, led the American Federation of Labor to bar all persons of Asian descent from membership in the union.

The following year, in 1908, a “Gentleman’s Agreement” was reached between the governments of Japan and the U.S. to limit total Japanese immigration. While families of Japanese immigrants already in the U.S. could come, such as Rev. Hirota’s own wife and children, all others would be barred entry.

Church attendance at Pine Street remained steady or slightly growing as it had during the period after the fire, but the new legal situation meant a corresponding increase in school enrollment did not happen. Rev. Hirota continued to work with the church, the school, and the publishing house for another nine years.

In 1917, Rev. Hirota was reappointed to a church in Honolulu, as pastor and director of the Japanese mission work on the island. He was well received and remembered as the first missionary to the Japanese on Maui many years before. The Friend, a Hawaiian Christian newspaper, wrote at the 1917 dedication of a Japanese Methodist church in Waipahu, “Mr. Hirota is a happy addition to our Christian forces in Honolulu; he is a forceful speaker and was listened to with great interest.”

In 1921, Rev. Hirota was moved to Sacramento and began serving as president of the Japanese Evangelistic Society. All Japanese-related work would become even more difficult beginning in 1924, when the Immigration Act banned all immigration from Asian countries, including Japan. The Immigration Act was primarily responsible for the closure of the Anglo-Japanese School in 1927.

Still, Rev. Hirota served faithfully where he had been appointed, moving on to churches in Yakima, Washington (1930), and Bakersfield, Calif. (1936), up to the time of his retirement in 1937. Upon retirement, he moved back to San Francisco, where he became active again at the church he had pastored for many years on Pine Street.

In 1942, an executive order signed by President Roosevelt forcibly removed over 120,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes. Rev. Hirota, then 74 years old, was sent with his family to a detention camp in Utah’s Sevier Desert (Topaz Relocation Center) until World War II ended in 1945. The clergy roll in the conference journal from 1942 lists all of the Japanese pastors in the “Military Zone,” and notes, in somber tones, that they were excused from ministerial duties while so located.

Returning to his home in San Francisco after release from three years of unjust detention, Rev. Zenro Hirota died on Nov. 18, 1948, at age 80, and was buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California.

Among the first waves of Japanese immigrants to the United States, and among the first Japanese Methodists to be ordained and serve in the Methodist Episcopal Church, Rev. Hirota distinguished himself through consistent and diligent service and witness to the Gospel. He did so while facing many obstacles, including the destruction of church and school facilities, xenophobia and discrimination against his people and those he sought to reach with the Gospel, the end of Japanese immigration to America and, as a final insult, losing all property, assets and rights in a detention camp during World War II. Through all of this, he remained loyal to Christ, to his mission, and to his colleagues, and they continually showed their appreciation for his service.

Three living United Methodist bishops of Japanese descent (see sidebar above) and countless Japanese American United Methodists can give thanks for Rev. Hirota as a pioneer whose persistence in the face of adversity helped build unbroken connections in ministry and faithful witness to this day.

This content was produced by Ask The UMC, a ministry of United Methodist Communications.