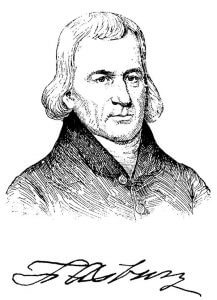

While many know Francis Asbury as the father of American Methodism and a church leader, he also was a lifelong missionary, arriving in and traveliing throughout America to share the Gospel.

Asbury was a missionary in the style of those sent by Jesus in the Gospel of Luke, chapter 10. Those very first Christian disciples were told to take the news of God’s kingdom, but to take no baggage, to depend upon the hospitality of those they encountered.

No Home, No Office

Asbury had no episcopal residence, no home of any kind, no office, no staff, and no ecclesiastical baggage. He owned some books and a series of horses that he rode, or pulled his carriage as he aged, across the tens of thousands of miles he traveled first in England’s American colonies and then, after the Revolutionary War, in the young United States. He depended on the hospitality of friends or strangers.

In time, across more than 40 years as a circuit rider, the bishop became a sort of celebrity—often called an “American saint.” Methodism flourished, so that there were 214,000 American Methodists by the time of his death.

Asbury was sent as a young lay preacher to America by John Wesley, Methodism’s English founder, and the British Methodist Conference at the request of lay Methodists who were organizing themselves into “societies,” later to become congregations. He was one of six young missionaries sent to the colonies in the 1770s. At the 1771 conference of British Methodists, meeting in Bristol, Mr. Wesley said “Our brethren in America call aloud for help. Who will go?” Asbury would become one of the missionaries sent — and the only one to remain through the American Revolution.

The earliest American Methodist societies were in the New York City, Philadelphia, and Maryland areas. The young English missionaries, with their plain sermons about the love and forgiveness of God in Jesus Christ, found receptive audiences. And the model of the interpersonal and community support provided by the Methodist “classes”— an early version of small-group ministry– struck welcome cords in rural and urban areas.

Asbury was ordained and appointed bishop by Bishop Thomas Coke at the Christmas Conference establishing the Methodist Episcopal Church of the United States at Baltimore, Maryland, in the winter of 1784.

Preached to All

Asbury and his lay-preacher colleagues may not have been formally commissioned as missionaries or, initially, ordained as clergy, but they were committed evangelists. Asbury considered it his God-ordained responsibility to tell everyone he could about the salvation available in faith through God’s grace in Jesus Christ. He wanted to reach everyone — all men and women, of all ages, all races, and all backgrounds. To the early Methodists, God’s love for all meant God’s love for ALL. There were no exceptions.

Asbury preached to white and Black and racially mixed audiences — male and female — across the whole of his ministry, sometimes negotiating with Southern white plantation owners to let Methodists preach to their enslaved people.

Impact of Slavery

Slavery was a divisive, hotly contested issue in early American Methodism. Asbury, like John Wesley, deplored slavery and slave holders were declared ineligible for Methodist membership at the1784 conference formalizing the Methodist Episcopal Church in the USA. But economic force soon mitigated the action, and slavery would nag at the soul of the church until and after it ripped it into northern and southern branches in the early 1840s. Unification was not achieved until 1939, and formal segregation would hang on in some regions until the creation of The United Methodist Church in 1968.

As much as he hated slavery, Asbury was not a social reformer. He did personally ask George Washington to free his slaves and promote abolition — with no success — but never led an anti-slavery crusade. In fact, Asbury’s generation of American Methodists was not deeply engaged in social outreach of any kind, as was John Wesley. Perhaps it was, as some historians suggest, American culture and religion were not equipped to take on social causes until the middle of the 19th century.

Saving Souls

Mission to Asbury mean soul-saving, and missionaries for him were most often circuit riders pushing farther and farther onto the Western frontier. When a late 18th or early 19th century Methodist preacher — mostly ordained by then — was no longer willing to “travel,” he was “located,” which usually meant he wanted to marry and settle down, taking up a trade that would feed a family and, in effect, leaving the ministry.

One of Asbury’s heartaches was keeping enough “traveling” preachers on horseback to meet the needs of an expanding movement. Married men could not support a family on the pittance a circuit rider was paid. Asbury at times found some of his best preachers, his most effective missionaries, leaving the Methodist connection to become settled Episcopalian rectors.

Asbury did not anticipate or speculate on what would after his death come to be called “foreign missions” — meaning outside of the United States, although later, after a Methodist Missionary Society was organized in 1819, some work on the West Coast would be classified as “foreign.” He saw the missionary vocation as following a domestic pathway. He did advocate “missionary offerings” to start new circuits.

Asbury failed to share the enthusiasm of his fellow bishop, Thomas Coke, and some younger preachers, for mission ventures into Canada and the Caribbean. Both of those areas would be left to the British Methodist Church to evangelize. Asbury’s eyes focused on his adopted country.

Always frail, often sickly, Asbury kept up his arduous missionary travels well into old age. He attended eight annual conferences in 1815. He preached his last sermon in Richmond, Virginia, on March 24, 1816. On March 31 of that year, Francis Asbury died peacefully at the home of the George Arnold family in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, and was buried on the farm there. His body was reburied in Baltimore by order of the 1816 General Conference. Historian John Wigger writes that on May 10 of that year, 20,000 to 30,000 people followed the coffin to the new grave site.

Postscript

Three years before his death, Asbury wrote a farewell letter to the American Methodists. As befitting his talent and responsibilities, it focused in large part on the structure and organization of future Methodism. He strongly advised the U.S. church to have only three bishops, who would always be available to travel, preach and oversee the connection.

Always the missionary, Asbury argued that bishops and other preachers should always be on the move.

Adapted by the author, Elliott Wright, from his article of May 19, 2016, from the United Methodist General Conference in Portland, Oregon. The conference marked the 200th anniversary of Asbury’s death.