Editor's note: This piece was presented as part of the Methodist Mission Bicentennial in 2019.

Say the name John Stewart and a person is likely to think of the former host of The Daily Show, the smart-alecky political satirist of cable TV fame. But did you know there’s another John Stewart (1786-1823), a notable in Methodist history? Though one of the UMC’s most important forebears, this John Stewart flies under the radar—if he even gets a mention at all.

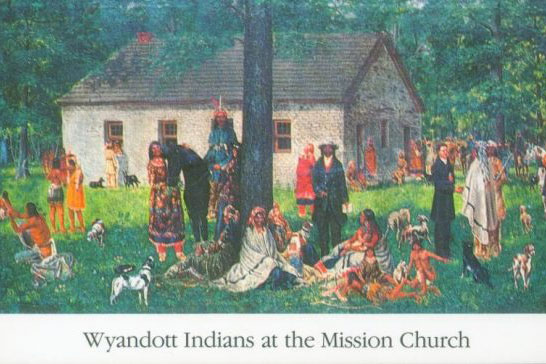

The Methodist John Stewart is a key figure in the story surrounding the Wyandott Indian Mission in Upper Sandusky, Ohio. The Wyandott [1] Indian Mission is one of the 49 United Methodist Heritage Landmarks, the most sacred places in global United Methodism.

A contemporary of early American Methodist Episcopal Church leaders like Francis Asbury, Richard Whatcoat, and William McKendree, Stewart was our original missionary, inspiration and impetus for the first permanent denominational mission enterprise. His outreach engaged Native Americans from the Wyandott (or Huron) nation settled in northern Ohio after the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Rediscovering John Stewart’s impact, the agenda of the General Board of Global Ministries (GBGM) will include Stewart as a key figure when marking their bicentennial in 2019.

Traveling to the Heritage Landmark with colleague General Secretary Thomas Kemper and members of the GBGM team, we got to know more about Stewart, his calling, vision and life’s work at the Wyandott Indian School. We left the visit shaking our heads in astonishment and with some chagrin that we did not previously know or lift-up this difference-making disciple.

John Stewart was born in Virginia to Baptists of mixed European and African descent (1786). Leaving home to move to Ohio, he began a long personal journey through difficult spiritual wilderness. Robbed of all his possessions during the trek, he turned to alcohol to dull the pain. Drinking, dissolute living, and depression brought him to the brink of death. He thought about ending his life until one day he heard a voice calling his name. He saw no one but to him, the voice was real enough that it brought him to his senses. If this story was being told in a feature film, the Negro Spiritual “Hush, Hush, Somebody’s Calling My Name” would be playing in the background.

The era of John Stewart’s life coincided with the popularity of camp meetings—evangelistic, religious, revival gatherings held in frontier forest clearings where enthusiastic preaching, inspired singing, impassioned praying, deep personal reflection and come-to-Jesus conversions were commonplace. American Methodist evangelism flourished in the camp meeting environment and indeed much of the MEC’s growth in its early years was seeded in these early camp meetings. The journals of the likes of Francis Asbury and William McKendree are full of references to camp meetings and their dramatic effects on people’s lives.

John Stewart’s turning-point came at a camp meeting. While in prayer at a camp meeting, Stewart heard a voice again. It said: “Declare my counsel faithfully.” By these words, Stewart sensed God saying to him ‘tell other people about me!’

For a time, Stewart struggled against this calling, to the point that the inner turmoil caused serious illness. Fearing death, he vowed to commit himself to mission work among Native Americans and to follow this calling to the northwest Wyandott country in and around today’s Upper Sandusky, Ohio.

Those who write about Stewart’s life say he “sang and preached his way to the Delawares on the way to the Wyandotte.” Don’t you love that visual? His preaching was interspersed with singing. It is so Methodist! I wonder what he sang? Perhaps:

Love Divine all loves excelling, joy of heaven to earth come down,

fix in us thy humble dwelling, all they faithful mercies crown.

Jesus thou art all compassion, pure unbounded love thou art,

visit us with thy salvation, enter every trembling heart.

Apparently, the enthusiasm expressed in his ministry was contagious.

After reaching the Wyandott, he was befriended by another person of African descent, Jonathan Pointer. Pointer was first captured by and now living with the Wyandot. Pointer, fluent in Wyandott language and interpreter for and confidant to Tarhe, the paramount Wyandotte chief, was invaluable in helping John Stewart connect.

Stewart’s preaching and singing resulted in friendship and religious conversion by Wyandott chiefs and leading women in their community. They said the Christian message John Stewart presented brought them inner peace they hadn’t known before. This peace brought reconciliation to estranged and fractured relationships in the tribe, not to mention the significance of the Methodist’s temperance message at a time when “strong drink” (something Stewart knew about) was becoming a serious problem in their tribal community.

With neither money nor credentials, only the passion of his experience of God’s grace and enthusiasm grounded in his calling, Stewart began work with the Wyandott in the winter of 1816. The obstacles he faced were formidable. A black man was perceived as an inferior human being in the eyes of many whites—not to mention the law—despite Methodism’s egalitarian appeal and engagement of blacks. The call to mission Stewart heard and accepted from “the voice” was to people with their own experience and reasons understandably suspicious of outsiders.

Stewart also faced impediments from other religious groups already working the area. Stewart’s early success with the Wyandott made missionary competitors envious to the point of accusing him of dishonesty and threatening to expose him as a runaway slave—a serious, life-threatening, incarcerating, deportable charge. They said he had no credentials to follow the call he’d embarked on. Through all this, Stewart persevered with courage and determination.

The Methodist quarterly conference licensed John Stewart a “missionary pioneer” in 1818 on lands “allotted to” the Wyandott by the US government. The following year, the Ohio Conference established an official mission to the Wyandott. The Methodist Episcopal Church supported his mission work financially and appointed missionaries to assist him. Stewart’s work and example inspired the formation of The Methodist Missionary Society in 1820, the forerunner to today’s General Board of Global Ministries.

John Stewart’s health was never robust and he found he could do less and less even though he was still a relatively young man. His friends collected enough money to buy him a small farm, where he lived with his wife until his death in 1823 at 37 years of age. By the time he died, Stewart noted he had not only “declar[ed] my counsels faithfully,” his personal experience of the life-changing love of God in Jesus Christ had brought many Wyandott to experience the same. His passion and vision started a mission school in Upper Sandusky not FOR but WITH the Wyandott. This mission school was NOT the “kill the Indian save the man,” type of Indian schools Methodists and other churches were infamously and perilously party to 25 years later. The Wyandott Indian Mission School of John Stewart and those who followed in his footsteps was a school run by blacks, whites, and Indians side by side. In this school Native American culture and identity would not be shamed but be a key in coming-together, established in the vision of a black man to have a school and a church together.

The words he spoke to his spouse, on his deathbed, embody his testimony from the first voice he’d heard decades before to and through his following its lead: “be faithful.”

As a result of his faithful efforts, John Stewart was adopted into the Wyandotte nation. Thirty years later, a Methodist Church (now UMC) was named in his honor. In more recent times, the church sponsors a Native American Awareness Day in the Upper Sandusky public schools, bringing local and national leaders of the Wyandott nation in for a day of immersion in Wyandott language, culture and history. And all because this extraordinary Methodist missionary John Stewart inspired the conviction that Wyandotte life has been and still needs to be woven into the mainstream of Upper Sandusky life.

In this spirit, GBGM will, as part of its bicentennial celebration in 2019, turn the title of the land of the Wyandott Indian Mission back to the Wyandotte Nation—its original owners. Sadly, like most American stories with the indigenous peoples, the Wyandott, despite John Stewart and the Mission School’s positive influence, were forced from Upper Sandusky due to increasingly intolerant white-European encroachment and the enforcement of an 1830 Indian Removal Act in what amounted to a another “trail of tears.”

John Stewart’s story gets at the heart of Christian mission. Words like acceptance, tolerance, collaboration, and breaking down barriers come to mind. Mission and ministry WITH instead TO and FOR others come to mind and stands in stark contrast to words like arrival, assessment, exploitation, occupation, forced assimilation or alienation—all too common in the paradigm of the history of Christian mission.

Stewart’s experience of “coming to his senses” because of God’s goodness and love compelled him to do difference-making good for others. To have a sense conversion and calling so strong it defied internal and external perceptions of inferiority, insurmountable obstacles, unknown terrain, lack of credential and ill health.

I grew up in an era (1950s and 60s) when the idea of being a missionary was to be sent to some far off, primitive land. Later in my life, the church recovered a sense that missions could and also needed to be in cities and rural areas here in the US where human need is as great as any far-off land. I have come to realize that mission is neither near nor far. It is, in the contemporary expression of the General Board of Global Ministries, an “everywhere to everywhere” enterprise.

Even more than that, mission is embodied in a person like John Stewart. Mission in Methodist history is often centered in and motivated by people experiencing God’s grace, agonizing over their life circumstances and surroundings and sensing God meeting them right where they are. God’s love calls to the best in them and calls the best out of them, to be holy difference-makers. Mission is moving-out and ahead, not being able to sit still because of what God has done and will do.

“Declare my counsel faithfully” the voice said to John Stewart. Go tell what I have done for you. Go tell my story, the voice still says. Is that voice speaking to you? Where you are?

God open our ears.

Wyandott Chief Billy Friend shared the mission statement of the cultural committee of the nation: “to preserve the future of our past.” I have never heard a better mission statement for all of us in the history and mission business of The United Methodist Church.

[1] In researching this article the name Wyandott appears interchangeably in at least three different forms – Wyandot, Wyandott and Wyandotte. I have chosen the form Wyandott because of its longstanding use in relationship to The Wyandott Indian Mission School as a United Methodist Heritage Landmark.

Bibliography:

Finley, James B. Life Among the Indians; Or Personal Reminiscences and Historical Incidents Illustrative of Indian Life and Character. Printed at the Methodist Book Concern in Cincinnati for the author, 1857. Reprinted Freeport NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971.

Love, N.B.C, John Stewart Missionary to the Wyandots. New York: Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church, 1900.

Marsh, Thelma R., Moccasin Trails to the Cross: A History of the Mission to Wyandott Indians on the Upper Sandusky Plains (Upper Sandusky, OH, John Stewart United Methodist Church).

Excerpt: Testing and Trials http://www.wyandot.org/stew2.htm

Excerpt: John’s Letter to the Wyandot http://www.wyandot.org/stew3.htm

Excerpt: Stewart Returns to the Wyandot http://www.wyandot.org/stew4.htm

Mitchell, Joseph, Missionary Pioneer, or A Brief Memoir of the Life, Labors and Death of John Stewart, Man of Colour (Austin: The Pemberton Press, 1969; Reprint of the 1827 original).

Stockwell, Mary, The Other Trail of Tears: The Removal of the Ohio Indians. (Westholme Publishing, Yardley, Pa. 2016).

The Rev. Fred Day served as General Secretary of The United Methodist General Commission on Archives and History from 2014-2020.