Besieged by death threats, racial abuse and physical danger, somehow Jackie Robinson never publicly lost his composure during the 1947 Major League Baseball season, when he integrated the league.

It was an amazing achievement, given Robinson’s reputation in the Negro baseball league as having a “temper like a rattlesnake,” said Michael G. Long, co-author with Chris Lamb of “Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography.”

Robinson had a little-known ally helping him stay stoic and perform well through the ordeal. He had faith.

After a tense day at the ballpark, Robinson would head to his bedroom, get on his knees and pray for strength and courage, his wife Rachel Robinson told Long.

“His faith acted as a source of comfort, but also a challenge,” Long said. “(He was) comforted when he felt tension. It also challenged him to … not fight back.”

Learn more

'God's a Methodist'

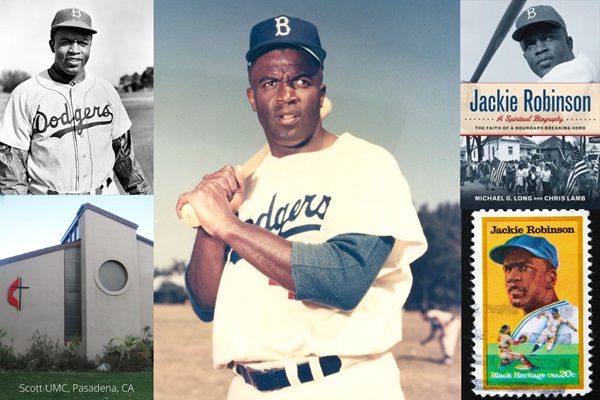

Robinson grew up attending Scott Methodist Church in Pasadena, California. But his Methodism and relationship with the Rev. Karl Everette Downs have been downplayed or ignored in many stories and biographies.

There’s one scene in “42,” the film about Robinson starring Chadwick Boseman, that mentions the connection.

But it’s a good one.

Branch Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodgers executive responsible for recruiting Robinson to break the color barrier, is played by Harrison Ford. In one scene, he declares: “Robinson’s a Methodist. I’m a Methodist. God’s a Methodist. We can’t go wrong.”

There’s no confirmation that Rickey actually said that, but it’s clear that their shared Methodist heritage was a factor in Robinson’s selection.

Grace under pressure

Robinson had a .311 lifetime average, won rookie of the year and most valuable player and helped the Dodgers to a World Series victory in 1955. He’s in the Baseball Hall of Fame and his number 42 was retired by MLB in 1997.

“What's most remarkable to me is that Robinson put those stats up while he was under death threats,” Long said.

Robinson played much of his career under death threats, as well as experiencing abuse from racist fans and other players. Even some of his Dodgers teammates signed a petition to Rickey in 1947 protesting the hiring of a Black player.

Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman famously hurled the N-word and other racist epithets at Robinson, and encouraged his players to do so, during a game in Brooklyn on April 22, 1947.

“Those (incidents were) really psychologically damaging,” Long said. “I don't want to downplay that. But going out onto the field thinking that somebody in the stands might shoot you is on a different level.”

But Robinson held his desire to retaliate in check in the interests of the greater good. If he had failed, many Black baseball players wouldn’t have gotten a shot in the big leagues.

Robinson's Methodist roots

Robinson attended Scott Methodist Church as a boy at the insistence of his mother, Mallie Robinson. The arrival of Downs in 1938 to the church was a game-changer for Robinson, who was already a local sports hero as a youth.

“What he did was to inject some of the Black social gospel into Scott Methodist Church,” Long said. “And he began to envision the church as having an important role in the community, and Robinson was really attracted to that.”

Mallie Robinson had already instilled racial pride in her son. She had an interpretation of the Adam and Eve story that Jackie took to heart.

“Mallie taught Jackie that Adam and Eve were originally Black,” Long recounted. “And then they were scared white when God caught them eating of the tree of knowledge of good and evil.”

The moral of the lesson was that Jackie’s black skin was a gift from God in which to take pride. His mother also taught him that it was God’s will to fight for freedom in the present, rather than await a better world in the afterlife.

Robinson continued that fight after his baseball career, as an associate of the Rev. Martin Luther King during the civil rights struggles of the 1960s.

Robinson died in 1972, of complications from heart disease and diabetes, at 53. He was nearly blind from the latter disease.

A paper released in April by three California researchers speculates that the real cause of Robinson’s death was racism.

“When a person repeatedly experiences the stress of racism, high levels of the stress hormone cortisol are released in the body,” wrote researchers Tamra Burns Loeb, Alicia Morehead-Gee and Derek Novacek in a story released by the University of California. “Elevated cortisol can lead to high levels of blood sugar, as seen in diabetes and high blood pressure.”

Jim Patterson is a Nashville freelance writer. Contact him by email.

This content was published July 14, 2021.