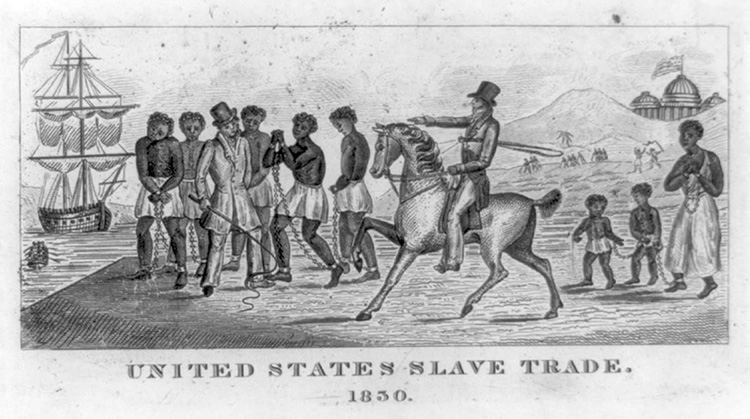

Racism has long been described as America’s “original sin.”

The 2020 killings of three African Americans — George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, who died at the hands of police, and Ahmaud Arbery, chased and shot to death by two individuals — sparked a national outcry against white supremacy and institutional racism, a protest that has now spread globally.

How is the UMC responding?

United Methodist Church leaders and members have joined those voices. The denomination’s Council of Bishops called for every United Methodist “to name the egregious sin of racism and white supremacy and join together to take a stand against the oppression and injustice that is killing persons of color.”

Other voices from across the denomination, from individual bishops and general agencies to students at Africa University in Zimbabwe, have also responded and issued statements.

The United Methodist Church has mounted a denomination-wide campaign, "United Against Racism," that urges its members not only to pray, but to educate themselves and have conversations about the subject, and to work actively for civil and human rights.

What does the UMC say about racism?

The United Methodist Social Principles state: “Racism, manifested as sin, plagues and hinders our relationship with Christ, inasmuch as it is antithetical to the gospel itself. … We commit as the Church to move beyond symbolic expressions and representative models that do not challenge unjust systems of power and access.”

The church recognizes the existence of white privilege as an underlying cause of inequality. It supports the concept of affirmative action to guarantee more opportunities for all to compete for jobs. It opposes racial profiling, mass incarceration, targeting of migrants and sentencing that disproportionately penalizes people of color.

The church also recognizes that racism, tribalism and xenophobia is a global problem and calls members everywhere to oppose such practices.

The church affirms that “all peoples and individuals constitute one human family, rich in diversity. … We recognize that religion, spirituality, and belief can contribute to the promotion of the inherent dignity and worth of the human person and to the eradication of racism.”

What is the church’s history with racism?

The United Methodist Church has a long history of concern for social justice, including speaking out against racial injustice, advocating for and working toward equality.

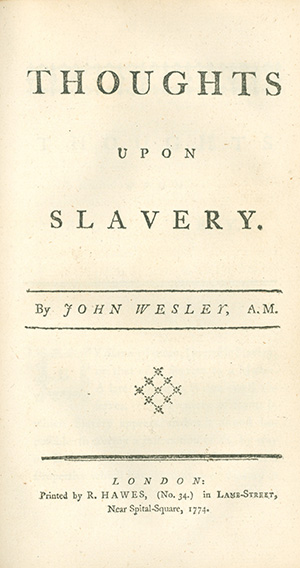

Methodism founder John Wesley was well known for his opposition to slavery. In 1773 he printed a pamphlet titled “Thoughts Upon Slavery,” in which he decried the evils of slavery and called for slave traders and owners to repent and free their slaves.

“Nothing is more certain in itself, and apparent to all, than that the infamous traffic for slaves directly infringes both divine and human law,” he wrote.

Wesley’s writings influenced political leaders of his day — including William Wilberforce, a British Parliament member who led a movement to abolish the slave trade. The last letter Wesley wrote, six days before his death, was addressed to Wilberforce, urging him to continue his work. In that letter, he lamented that “a man who has a black skin being wronged or outraged by a white man, can have no redress.”

However, Methodism has frequently struggled in addressing its own racism, which has been a defining force in shaping the Methodist movement in the United States from its earliest days. The denomination’s Book of Resolutions acknowledges the church’s shortcomings: “… racism has been a systemic and personal problem within the U.S. and The United Methodist Church and its predecessor denominations since its inception.”

African Americans were among the first Methodists in the United States, attending the early revival meetings. Two popular African American preachers — Harry Hosier and Richard Allen — were present at the 1784 “Christmas Conference,” where the Methodist Church was formally founded in America. Racist attitudes were already at work, as African Americans were forced to sit in church balconies and receive Holy Communion after their fellow white worshippers.

In 1794, Allen, a former slave, protested increasing segregation in worship services by leading most of the black members out of historic St. George's Methodist Church and founding Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. When the African Methodist Episcopal Church denomination formed in 1816, Allen became its first bishop. Other historically black denominations — African Methodist Episcopal Zion, Christian Methodist Episcopal, African Union Methodist Protestant and Union American Methodist Episcopal — emerged over the next several decades as a response to the denomination’s positions on slavery and its discriminatory practices.

Church positions on slavery led to divisions among white Methodists as well.

At the 1840 General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, James O. Andrew was elected bishop. Andrew owned slaves, despite the denomination’s anti-slavery stance since its founding.

The issue of a bishop owning slaves was a hotly contested debate at the following General Conference in 1844. When agreement could not be reached, a Plan of Separation was adopted. Two years later, the churches in the states where slavery was legal formed a separate denomination: The Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

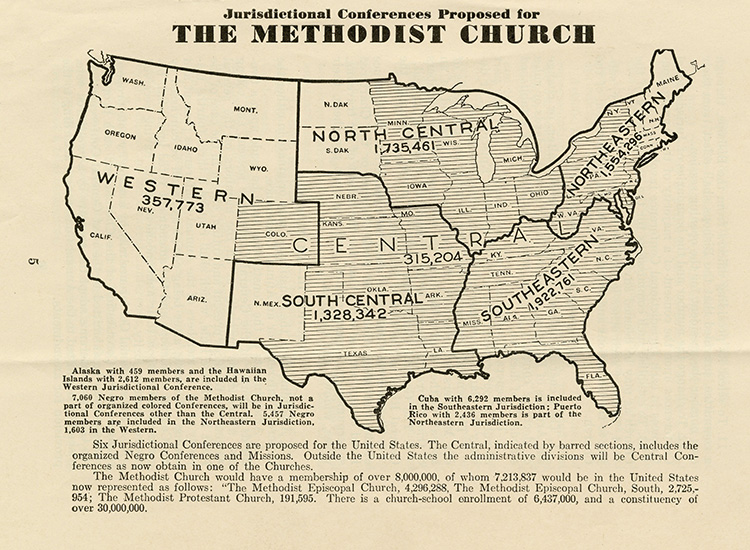

The 1939 union that created The Methodist Church from the Methodist Episcopal Church, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and Methodist Protestant Church also created the racially segregated Central Jurisdiction. The Southern church only agreed to union after a compromise created a regional structure based exclusively on race — not geography.

Nineteen black annual conferences were placed in the Central Jurisdiction and the white conferences were placed in five regional jurisdictions. Seventeen of the 19 black conferences voted against the 1939 Plan of Union.

The Central Jurisdiction was in place as the civil rights movement unfolded in the US in the 1950s and 1960s. Methodist clergy, including the Rev. Joseph Lowery and the Rev. James Lawson, were among the key figures in the movement. At the same time, Methodist bishops Paul Hardin and Nolan Harmon were among the white clergymen to whom Martin Luther King Jr. addressed his famed “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” a response to the clergymen’s public criticism of civil rights protests.

The Central Jurisdiction was not abolished until the 1968 merger with the Evangelical United Brethren to form The United Methodist Church. The EUB, which was not segregated, ultimately made abolishing the segregated institution a condition for union.

With the dissolution of the Central Jurisdiction, black United Methodists developed a plan for lobbying and presenting resolutions, including facilitating the creation of the Commission on Religion and Race. They also formed Black Methodists for Church Renewal, which launched initiatives such as Strengthening the Black Church for the 21st Century, the African-American United Methodist Heritage Center and the Black College Fund, which helps support the 11 historically black colleges and universities related to the church.

Delegates to the 2000 General Conference in Cleveland participated in a service of repentance for racism within the denomination and in 2004, General Conference delegates celebrated the African American witness and presence within The United Methodist Church and recognized "those who stayed" in spite of racism.

General Conference has held subsequent acts of repentance for other communities harmed by racism. In 2012, the act was for past injustice to Native Americans and other indigenous people. The 2016 conference featured a ceremony honoring the descendants of the victims of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, where U.S. troops led by Col. John Milton Chivington, a pastor in the Methodist Episcopal Church, charged on an unsuspecting, peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians, slaughtering more than 160 Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children, and elderly men.

How is the church working to dismantle racism today?

Three denominational agencies lead the church in this work:

Learn, Equip, Act

The General Commission on Religion and Race resources, trains and facilitates conversations to help churches dismantle racial discrimination in all its forms.

The General Board of Church and Society, located in Washington, advocates for legislative policies that support the church’s position on a variety of social issues, including civil and human rights in the areas of criminal justice reform, economic justice, immigration reform and opposition to the death penalty.

United Methodist Women name racial justice as an ongoing mission focus dating back to their inception. Their work has included campaigning against lynching in the early 20th century, monitoring hate crimes throughout the U.S., supporting legislation to end the “school-to-prison pipeline” and establishing a Charter for Racial Justice adopted by the entire denomination.

How are individual United Methodists called to respond to racism?

United Methodists acknowledge that racism denies the teachings of Jesus and our common, created humanity. United Methodists are called to continue to live out the baptismal vows “to resist evil, injustice and oppression in whatever forms they present themselves.”

The church states that “every annual conference, district, and local church should be engaged, intentionally, in being an anti-racist church, not merely on paper, but in action.”

United Methodists should advocate and work toward dismantling the unjust systems that cause, or even benefit from, continued inequality. Call out policies that disadvantage certain ethnicities, work for change and vote in ways that promote equal justice. Consider ways in which personal spending helps or hurts certain communities. Encourage fair hiring practices.

Changing beliefs, changing behavior and changing society are long processes that may never be complete. The people of The United Methodist Church will to continue to work for change in all three areas.

This content was produced by Ask The UMC, a ministry of United Methodist Communications.